"Anybody can do a

|

|||||||

Yesterday, we were in a department meeting discussing space, and when we started to discuss classroom scheduling a faculty member said, "Anybody can do a classroom and lab utilization study." That startled me and I thought for a moment before saying, “True, but some can do it better than others.” By “better” I mean that the person doing the analysis understands and can explain the complexity and interrelationship among dynamics such as faculty loading, average section size, number of course sections, number of faculty, number of classrooms and labs, space standards, best practices, building condition, institutional policies, and how effective the university has been in using this space resource. It’s not just hours per week compared to a standard that may or may not be applicable.

A typical instructional space (classroom, lab, and studio) utilization study is prepared using a data describing rooms in which scheduled course sections meet, and the data describing all the course sections scheduled in a semester. Usually there is a differentiation of rooms centrally controlled and those rooms that are controlled by a college, school or department. Computer labs are not classrooms even though they might be called that. Auditoriums are not classrooms, although they are typically scheduled as such. They have their own space category (FICM 610 Assembly) and multiple uses beyond scheduled instruction.

Three types of calculations are typically prepared using the inventory of spaces and the Registrar’s course file: the hours per week that a room is scheduled; the percent of seats that are occupied when scheduled, and the amount of net square feet per seat in the room. These calculations are then compared to utilization guidelines or standards that have been approved by various states and agencies, or other normative standards.

That faculty member was correct, anybody can do a classroom and lab utilization study. But not everyone can do it well.

Let’s start with the utilization guideline that is almost universally accepted with little variation. It was developed 71 years ago in a 1948 California study of higher education and space efficiency. The study assumed that 100% classroom utilization was impossible and that ideally, in a 45-hour weekly scheduling window, the typical classroom should be scheduled 65% of the time – or 29 hours per week. That assumption has been modified over the years and most states use 30 to 32 hours today.

Given what we now know about cognitive research and how students learn, changes in pedagogy, technology, and active learning, the guidelines should be used carefully and, in some cases, ignored.

Not everyone knows that they should clean-up the Registrar’s course file before using it. The file’s data should record the facts after the drop/add period. All TBD courses should be eliminated. All cross-listed courses identified and combined. All conflicts should be eliminated.

Instructional labs need special attention particularly if the departments schedule their own labs and report that information to the Registrar. Not all departments are diligent about reporting. It is a problem if a lab is scheduled as a classroom as well as a lab, or if the department schedules a classroom as a home base and divides the course into smaller lab sections without reporting the lab.

Not everyone knows that combining the day and evening into a larger scheduling window of approximately 70 hours per week actually can hide or mask scheduling problems. Since this generalizes the utilization across all 70 hours it is difficult to determine whether there is a day time scheduling issue or an evening issue. For some universities, the utilization in the evening is sufficiently higher than in the day generating a need for additional classrooms. The scheduling window in the evening is only about 25 hours per week and a heavy evening program can easily create a utilization problem. Some states and some universities actually require this extended scheduling window without understanding the implications on accurately diagnosing a problem.

Not everyone knows that all schedulable classrooms and labs should not be combined and assessed with one guideline as one university has done touting how efficient they are. The high utilization of classrooms is mitigated by the low utilization of labs, and so the overall utilization is lower.

Classrooms are relatively generic and interchangeable. All classrooms can be assessed in the same way using an appropriate set of utilization guidelines. Labs, on the other hand, are discipline specific and cannot be lumped together. They are not interchangeable. Labs have a lower utilization because each lab type has its own need for set-up before class, and its own time for clean-up afterwards. An organic chemistry lab usually has one fume hood for every two students. If there is only one course section or 10 course sections, the lab is still a required space but the utilization certainly will be different.

Not everyone knows that they should not stick dogmatically to some utilization standards particularly those that are now over 70 years old. Most small liberal arts colleges with comparatively few sections will find it difficult to achieve the 30 hours per week standard, while most large Universities can easily approach or exceed that target. In the end, it is a choice made by the institution. If extracurricular activities are important, and if part of the mission is community service, then a lower utilization target may be desirable. If on the other hand, the university has a large enrollment, with many course sections and a need to move a large number of students through the curriculum, then a higher utilization target might be appropriate.

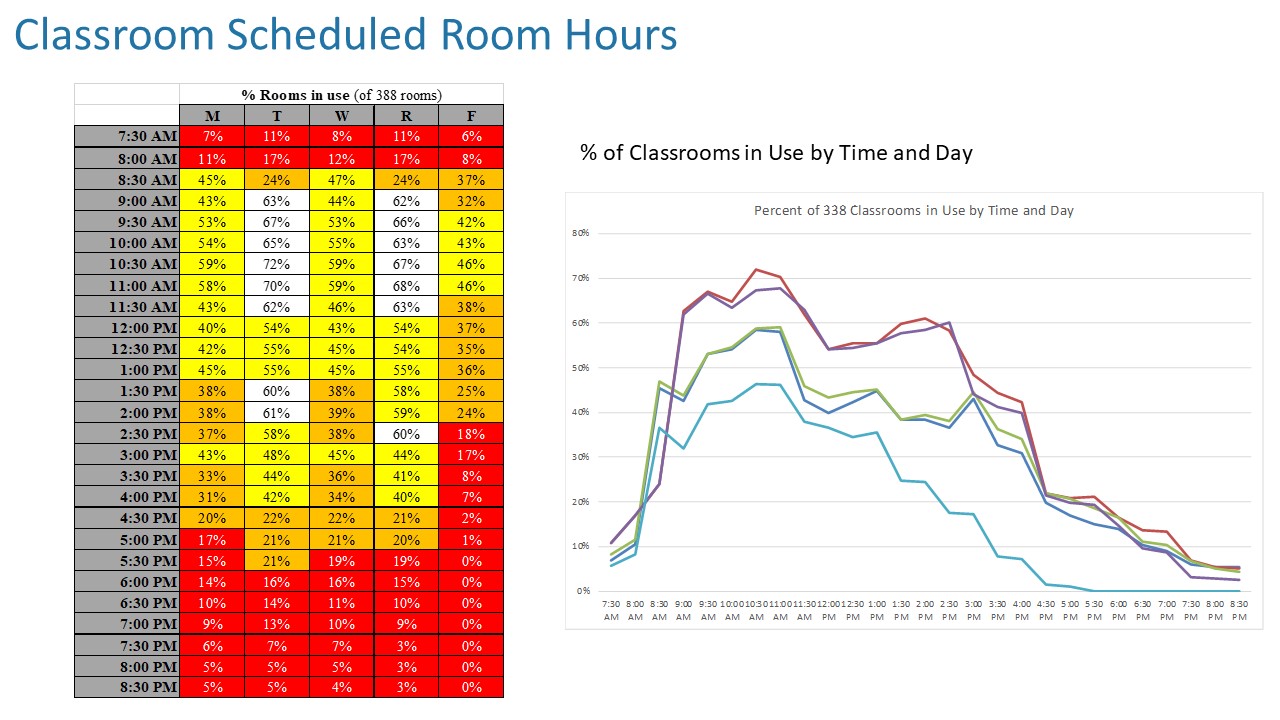

Not everyone knows which policies to establish, change, or recommend depending on the results of the utilization study and the institution’s particular situation. One easy policy is to minimize the number of classrooms that are not centrally scheduled since department classrooms are usually less well utilized. Another policy to consider is standardizing the schedule so that there are fewer start times and fewer ad hoc time slots. Another policy is to give the Registrar more authority to schedule courses where and when (if possible) they are appropriate. In order to avoid the peak period crush, create policies to require or incent departments to schedule some proportion of courses outside of peak time which is usually between 10:00 am and 2:00 pm.

Not everyone knows which incentives to establish in order to modify course scheduling and classroom utilization and provide an environment that encourages faculty and students to embrace focused change. One incentive is to offer students a reduction of tuition if they take courses outside of peak times. Another incentive is to establish a sliding fee for departments for when they schedule courses. No fee for off-peak, and a higher charge the closer they schedule in the peak time.

Some universities encourage the switch from department ownership to central control by assuming responsibility for maintenance costs and technology upgrades. Another approach is for the university to assume control of a department classroom if the utilization does not reach an agreed upon target.

So, yes, anybody can do a classroom and lab utilization study. It’s the implications of the calculations that are the key. What do the numbers mean? How should the institution respond? What, if anything, needs to change? Is it a question of:

So, yes, anybody can do a classroom and lab utilization study, but not everybody knows how to help a college or university decide the best approach for improving the situation. Dober Lidsky Mathey’s higher education campus and facility planners provide insider-grade experience to solve your complex and sensitive space and building problems. Choose the right specialist for the project.

|

|||||||

|

||||||||

© Copyright 2019

|

||||||||