|

||||||

|

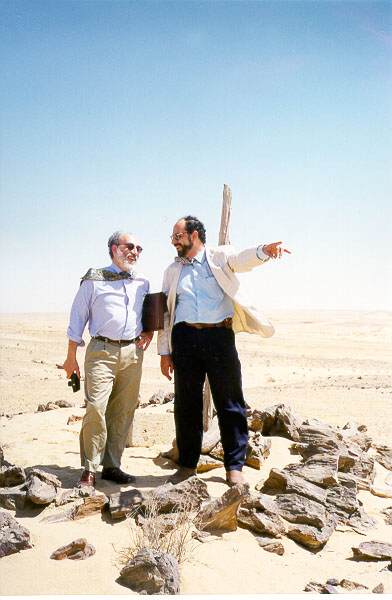

In this issue, George discusses how to manage expectations during a planning or programming process. Arthur describes a key college or university person in the planning process. This person, the Project Shepherd, is the link between the institution, the planning consultants, and ultimately, architect/engineer team.

If you have reactions or ideas to share, please let us know what you think by e-mailing: editor@dlmplanners.com |

||||||

|

When we initiate planning studies – discussing process, deliverables and desired results with our clients, we are often asked, “How will your process manage expectations?” Many campus leaders are clearly concerned that a participatory planning process can open a can of worms by encouraging faculty, staff and students to think “too big”, resulting in a planning agenda far too ambitious for the institution’s limited capital dollars. As the planning proceeds, we are just as often surprised to uncover the opposite problem – that of thinking “too small”. Most of the campus user representatives we speak to have a highly-refined sense of institutional capabilities, and often are focused simply on “fixing what’s broken” and not on re-inventing, or transforming their campus. In practice, one hallmark of the participatory planning model is that when you truly engage a client group, it strengthens a sense of shared responsibility and a realistic understanding of what’s possible in the planning horizon under discussion.

To realize this benefit of participation, several steps should be taken starting prior to the active process and ending after the final report is complete: Plan for Planning

During the Planning Process

At the End of the Planning Process

An engaged community facilitates plan implementation, as more people are aware of the plan, its rationale and recommendations. The unexpected key to managing expectations is true participation.

George Mathey | |||||||

| NEWS | ||||||

New Projects

Completed Projects

Retraction on Issue 21

|

For all you adventurers Erika spent some time this summer exploring Vermont's Northeast Kingdom, hiking scenic trails, canoeing on Seymour Lake, and roasting marshmallows over a campfire.

|

|||||

|

||||||||

© Copyright 2009

|

||||||||